Choose a Category

- Ancient Documents

- Ancient Egypt

- Ancient Greece

- Ancient Israel

- Ancient Near East

- Ancient Other

- Ancient Persia

- Ancient Portugal

- Ancient Rome

- Archaeology

- Bible Animals

- Bible Books

- Bible Cities

- Bible History

- Bible Names A-G

- Bible Names H-M

- Bible Names N-Z

- Bible Searches

- Biblical Archaeology

- Childrens Resources

- Church History

- Evolution & Science

- Illustrated History

- Images & Art

- Intertestamental

- Jerusalem

- Jesus

- Languages

- Manners & Customs

- Maps & Geography

- Messianic Prophecies

- Museums

- Mythology & Beliefs

- New Testament

- People - Ancient Egypt

- People - Ancient Greece

- People - Ancient Rome

- People in History

- Prof. Societies

- Rabbinical Works

- Resource Sites

- Second Temple

- Sites - Egypt

- Sites - Israel

- Sites - Jerusalem

- Study Tools

- Timelines & Charts

- Weapons & Warfare

- World History

61 Bible Translations

-

1599 Geneva Bible (GNV)

The Geneva Bible: A Cornerstone of English Protestantism A Testament to Reform The 1599 Geneva Bible... Read More

-

21st Century King James Version (KJ21)

The 21st Century King James Version (KJ21): A Modern Approach to a Classic Text A Balancing Act The ... Read More

-

American Standard Version (ASV)

The American Standard Version (ASV): A Cornerstone of Modern English Bibles A Product of Scholarly R... Read More

-

Amplified Bible (AMP)

The Amplified Bible (AMP): A Rich and Comprehensive Translation The Amplified Bible (AMP) stands out... Read More

-

Amplified Bible, Classic Edition (AMPC)

The Amplified Bible, Classic Edition (AMPC): A Timeless Treasure The Amplified Bible, Classic Editio... Read More

-

Authorized (King James) Version (AKJV)

The Authorized (King James) Version (AKJV): A Timeless Classic The Authorized King James Version (AK... Read More

-

BRG Bible (BRG)

The BRG Bible: A Colorful Approach to Scripture A Unique Visual Experience The BRG Bible, an acronym... Read More

-

Christian Standard Bible (CSB)

The Christian Standard Bible (CSB): A Balance of Accuracy and Readability The Christian Standard Bib... Read More

-

Common English Bible (CEB)

The Common English Bible (CEB): A Translation for Everyone The Common English Bible (CEB) is a conte... Read More

-

Complete Jewish Bible (CJB)

The Complete Jewish Bible (CJB): A Jewish Perspective on Scripture The Complete Jewish Bible (CJB) i... Read More

-

Contemporary English Version (CEV)

The Contemporary English Version (CEV): A Bible for Everyone The Contemporary English Version (CEV),... Read More

-

Darby Translation (DARBY)

The Darby Translation: A Literal Approach to Scripture The Darby Translation, often referred to as t... Read More

-

Disciples’ Literal New Testament (DLNT)

The Disciples' Literal New Testament (DLNT): A Window into the Apostolic Mind The Disciples’ Literal... Read More

-

Douay-Rheims 1899 American Edition (DRA)

The Douay-Rheims 1899 American Edition (DRA): A Cornerstone of English Catholicism The Douay-Rheims ... Read More

-

Easy-to-Read Version (ERV)

The Easy-to-Read Version (ERV): A Bible for Everyone The Easy-to-Read Version (ERV) is a modern Engl... Read More

-

English Standard Version (ESV)

The English Standard Version (ESV): A Modern Classic The English Standard Version (ESV) is a contemp... Read More

-

English Standard Version Anglicised (ESVUK)

The English Standard Version Anglicised (ESVUK): A British Accent on Scripture The English Standard ... Read More

-

Evangelical Heritage Version (EHV)

The Evangelical Heritage Version (EHV): A Lutheran Perspective The Evangelical Heritage Version (EHV... Read More

-

Expanded Bible (EXB)

The Expanded Bible (EXB): A Study Bible in Text Form The Expanded Bible (EXB) is a unique translatio... Read More

-

GOD’S WORD Translation (GW)

GOD'S WORD Translation (GW): A Modern Approach to Scripture The GOD'S WORD Translation (GW) is a con... Read More

-

Good News Translation (GNT)

The Good News Translation (GNT): A Bible for Everyone The Good News Translation (GNT), formerly know... Read More

-

Holman Christian Standard Bible (HCSB)

The Holman Christian Standard Bible (HCSB): A Balance of Accuracy and Readability The Holman Christi... Read More

-

International Children’s Bible (ICB)

The International Children's Bible (ICB): A Gateway to Faith The International Children's Bible (ICB... Read More

-

International Standard Version (ISV)

The International Standard Version (ISV): A Modern Approach to Scripture The International Standard ... Read More

-

J.B. Phillips New Testament (PHILLIPS)

The J.B. Phillips New Testament: A Modern Classic The J.B. Phillips New Testament, often referred to... Read More

-

Jubilee Bible 2000 (JUB)

The Jubilee Bible 2000 (JUB): A Unique Approach to Translation The Jubilee Bible 2000 (JUB) is a dis... Read More

-

King James Version (KJV)

The King James Version (KJV): A Timeless Classic The King James Version (KJV), also known as the Aut... Read More

-

Lexham English Bible (LEB)

The Lexham English Bible (LEB): A Transparent Approach to Translation The Lexham English Bible (LEB)... Read More

-

Living Bible (TLB)

The Living Bible (TLB): A Paraphrase for Modern Readers The Living Bible (TLB) is a unique rendering... Read More

-

Modern English Version (MEV)

The Modern English Version (MEV): A Contemporary Take on Tradition The Modern English Version (MEV) ... Read More

-

Mounce Reverse Interlinear New Testament (MOUNCE)

The Mounce Reverse Interlinear New Testament: A Bridge to the Greek The Mounce Reverse Interlinear N... Read More

-

Names of God Bible (NOG)

The Names of God Bible (NOG): A Unique Approach to Scripture The Names of God Bible (NOG) is a disti... Read More

-

New American Bible (Revised Edition) (NABRE)

The New American Bible, Revised Edition (NABRE): A Cornerstone of English Catholicism The New Americ... Read More

-

New American Standard Bible (NASB)

The New American Standard Bible (NASB): A Cornerstone of Literal Translations The New American Stand... Read More

-

New American Standard Bible 1995 (NASB1995)

The New American Standard Bible 1995 (NASB1995): A Refined Classic The New American Standard Bible 1... Read More

-

New Catholic Bible (NCB)

The New Catholic Bible (NCB): A Modern Translation for a New Generation The New Catholic Bible (NCB)... Read More

-

New Century Version (NCV)

The New Century Version (NCV): A Bible for Everyone The New Century Version (NCV) is an English tran... Read More

-

New English Translation (NET)

The New English Translation (NET): A Transparent Approach to Scripture The New English Translation (... Read More

-

New International Reader's Version (NIRV)

The New International Reader's Version (NIRV): A Bible for Everyone The New International Reader's V... Read More

-

New International Version - UK (NIVUK)

The New International Version - UK (NIVUK): A British Accent on Scripture The New International Vers... Read More

-

New International Version (NIV)

The New International Version (NIV): A Modern Classic The New International Version (NIV) is one of ... Read More

-

New King James Version (NKJV)

The New King James Version (NKJV): A Modern Update of a Classic The New King James Version (NKJV) is... Read More

-

New Life Version (NLV)

The New Life Version (NLV): A Bible for All The New Life Version (NLV) is a unique English translati... Read More

-

New Living Translation (NLT)

The New Living Translation (NLT): A Modern Approach to Scripture The New Living Translation (NLT) is... Read More

-

New Matthew Bible (NMB)

The New Matthew Bible (NMB): A Reformation Revival The New Matthew Bible (NMB) is a unique project t... Read More

-

New Revised Standard Version (NRSV)

The New Revised Standard Version (NRSV): A Modern Classic The New Revised Standard Version (NRSV) is... Read More

-

New Revised Standard Version Catholic Edition (NRSVCE)

The New Revised Standard Version Catholic Edition (NRSVCE): A Cornerstone of Modern Catholicism The ... Read More

-

New Revised Standard Version, Anglicised (NRSVA)

The New Revised Standard Version, Anglicised (NRSVA): A British Accent on Scripture The New Revised ... Read More

-

New Revised Standard Version, Anglicised Catholic Edition (NRSVACE)

The New Revised Standard Version, Anglicised Catholic Edition (NRSVACE): A Bridge Between Tradition ... Read More

-

New Testament for Everyone (NTE)

The New Testament for Everyone (NTE): A Fresh Perspective The New Testament for Everyone (NTE) is a ... Read More

-

Orthodox Jewish Bible (OJB)

The Orthodox Jewish Bible (OJB): A Unique Perspective The Orthodox Jewish Bible (OJB) is a distincti... Read More

-

Revised Geneva Translation (RGT)

The Revised Geneva Translation (RGT): A Return to the Roots The Revised Geneva Translation (RGT) is ... Read More

-

Revised Standard Version (RSV)

The Revised Standard Version (RSV): A Cornerstone of Modern English Bibles The Revised Standard Vers... Read More

-

Revised Standard Version Catholic Edition (RSVCE)

The Revised Standard Version Catholic Edition (RSVCE): A Cornerstone of English Catholicism The Revi... Read More

-

The Message (MSG)

The Message (MSG): A Contemporary Paraphrase The Message, often abbreviated as MSG, is a contemporar... Read More

-

The Voice (VOICE)

The Voice: A Fresh Perspective on Scripture The Voice is a contemporary English translation of the B... Read More

-

Tree of Life Version (TLV)

The Tree of Life Version (TLV): A Messianic Jewish Perspective The Tree of Life Version (TLV) is a u... Read More

-

World English Bible (WEB)

The World English Bible (WEB): A Modern Update on a Classic The World English Bible (WEB) is a conte... Read More

-

Worldwide English (New Testament) (WE)

The Worldwide English (WE) New Testament: A Modern Take on a Classic The Worldwide English (WE) New ... Read More

-

Wycliffe Bible (WYC)

The Wycliffe Bible: A Cornerstone of English Scripture A Revolutionary Translation The Wycliffe Bibl... Read More

-

Young's Literal Translation (YLT)

Young's Literal Translation (YLT): A Literal Approach to Scripture Young's Literal Translation (YLT)... Read More

Popular Articles

-

How to Track Your Reading List Effectively with BookPine?

For enthusiastic readers, managing a collection of books can become challenging. An expanding "to be... Read More

-

Chronology of the Prophets in the Old Testament

Deuteronomy 18 - "And if you say in your heart, 'How shall we know the word which the LORD has not ... Read More

-

The Books of the New Testament

John 14:26 - "But the Counselor, the Holy Spirit, whom the Father will send in my name, he will teac... Read More

-

The Table of Nations

(Enlarge) (PDF for Print) Map of the Origin of Nations and Races that were dispersed by God in Gene... Read More

-

Heavy Machinery Transport: How to Safely Ship Agricultural Tractors

Modern farming cannot be done without agricultural tractors, and their safe and efficient transporta... Read More

-

Map of the Journeys of Abraham

The Journeys of Abraham (Enlarge) (PDF for Print) - Map of Abraham's Journey with Trade Routes Map ... Read More

-

Map of the Route of the Exodus of the Israelites from Egypt

(Enlarge) (PDF for Print) Map of the Route of the Hebrews from Egypt This map shows the Exodus of t... Read More

-

Miracles in the Old Testament

Mark 6:52 - For they considered not the miracle of the loaves: for their heart was hardened. God did... Read More

-

The Outer Court

also see:The Encampment of the Children of IsraelThe Children of Israel on the March THE OUTER COURT... Read More

-

Kings of the Persian Empire

2 Chronicles 36:23 - Thus saith Cyrus king of Persia, All the kingdoms of the earth hath the LORD Go... Read More

-

Bible Maps

All Bible Maps - Complete and growing list of Bible History Online Bible Maps. Old Testament Maps T... Read More

-

The Biblical Foundations of Marriage Covenants and Ring Symbolism

The Bible portrays marriage as a lifelong bond built on love, faith, and commitment, reflecting God'... Read More

-

Ancient Nineveh

Ancient Manners and Customs, Daily Life, Cultures, Bible Lands NINEVEH was the famous capital of an... Read More

-

New Testament Cities Distances in Ancient Israel

Distances From Jerusalem to: Bethany - 2 milesBethlehem - 6 milesBethphage - 1 mileCaesarea - 57 m... Read More

-

Dagon the Fish-God

Dagon was the god of the Philistines. This image shows that the idol was represented in the combina... Read More

-

Map of Israel in the Time of Jesus

Map of Israel in the Time of Jesus (Enlarge) (PDF for Print) Map of First Century Israel with Roads... Read More

-

The Golden Table

The Table of Shewbread (Ex 25:23-30) It was also called the Table of the Presence. Now we will pas... Read More

-

The Priestly Garments

see also:The PriestThe Consecration of the PriestsThe Priestly Garments The Priestly Garments 'The ... Read More

-

The Book of Daniel

Introduction to the Book of Daniel in the Bible Daniel 6:15-16 - Then these men assembled unto the k... Read More

-

The Golden Lampstand

The Golden Lampstand was hammered from one piece of gold. Exod 25:31-40 "You shall also make a lam... Read More

-

The Golden Altar

The Golden Altar of Incense (Ex 30:1-10) The Golden Altar of Incense was 2 cubits tall.It was 1 cub... Read More

-

Tax Collector

Ancient Tax Collector Illustration of a Tax Collector collecting taxes Tax collectors were very des... Read More

-

The 5 Levitical Offerings

also see: Blood Atonement and The Priests The Five Levitical Offerings The Sacrifices The sacrificia... Read More

-

Shem, Ham, and Japheth

Genesis 10:32 - These are the families of the sons of Noah, after their generations, in their nation... Read More

-

Jesus Reading Isaiah Scroll

Illustration of Jesus Reading from the Book of Isaiah This sketch contains a colored illustration o... Read More

-

The Birth of John the Baptist

"But the angel said unto him, Fear not, Zacharias: for thy prayer is heard; and thy wife Elisabeth s... Read More

-

The Bronze Altar

also see: The Encampment of the Children of IsraelThe Children of Israel on the March The brazen a... Read More

-

Navigating the Modern World: Technology, Faith, Lifestyle, and the Evolving Human Experience

In a rapidly evolving world shaped by both timeless values and groundbreaking technology, individual... Read More

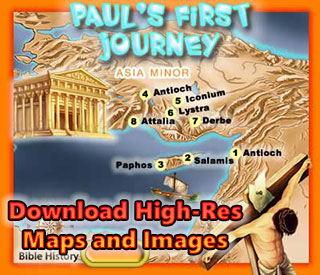

Explore the Bible Like Never Before!

Unearth the rich tapestry of biblical history with our extensive collection of over 1000 meticulously curated Bible Maps and Images. Enhance your understanding of scripture and embark on a journey through the lands and events of the Bible.

Discover:

- Ancient city layouts

- Historic routes of biblical figures

- Architectural wonders of the Holy Land

- Key moments in biblical history

Start Your Journey Today!