1599 Geneva Bible (GNV)

The Geneva Bible: A Cornerstone of English Protestantism A Testament to Reform The 1599 Geneva Bible... Read More

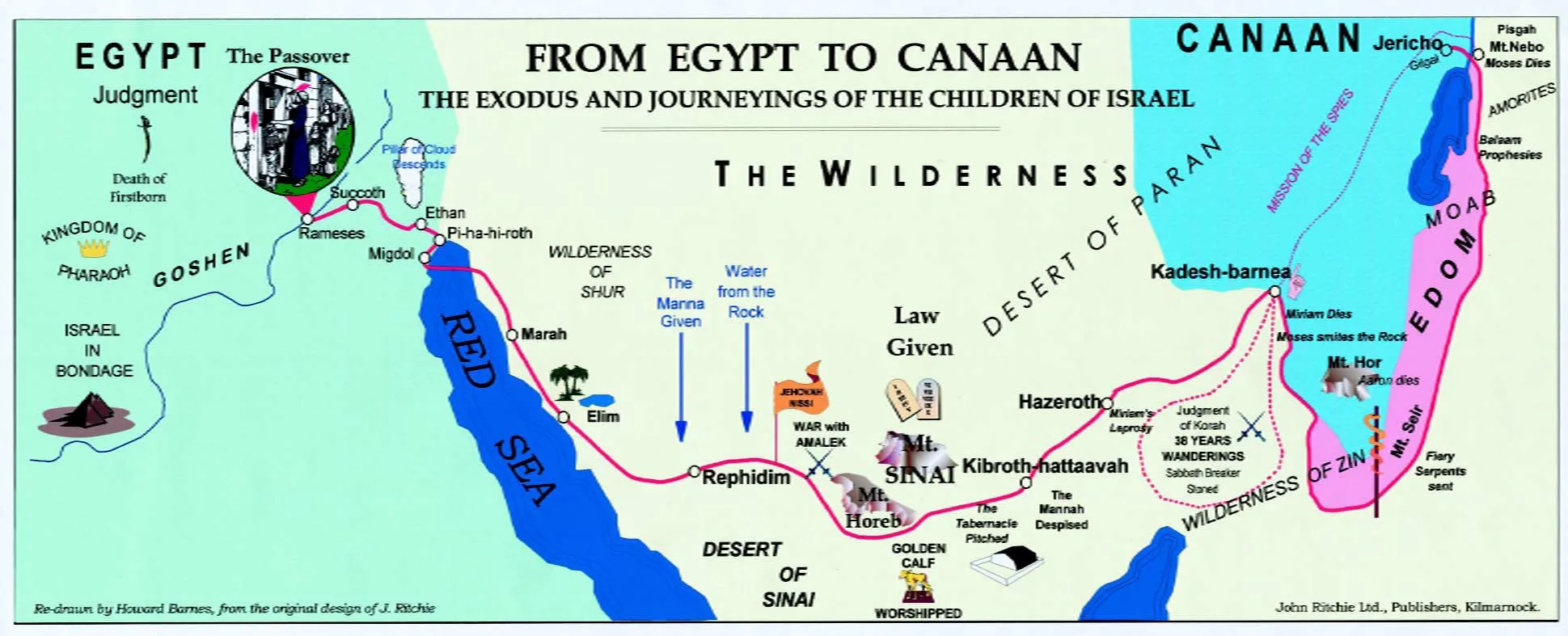

The journey of the Israelites from Egypt to Canaan, often referred to as the Exodus, is one of the most significant events in the history of the Israelites and in the biblical narrative. It is detailed primarily in the books of Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy in the Old Testament, and spans from the dramatic escape from Egypt to the eventual settlement in the Promised Land of Canaan. This post will take you through the key stages of this extraordinary journey, highlighting the geographical, spiritual, and political challenges that defined the Israelites' path, as well as providing relevant biblical references to ground the story.

The Israelites had been living in Egypt for over 400 years, initially migrating there during a famine in the time of Joseph (Genesis 47). Over time, they had grown numerous, which caused fear among the Egyptians, leading to their enslavement (Exodus 1:8-14). Under the leadership of Moses, chosen by God, the Israelites began their journey out of slavery. God sent ten devastating plagues on Egypt, the last of which, the death of the firstborn (Exodus 12), finally convinced Pharaoh to let the Israelites go.

The Exodus begins in Exodus 12, with the Israelites departing in haste, not even allowing their bread to rise, which is why they ate unleavened bread (Exodus 12:39). They journeyed from Ramses to Succoth (Exodus 12:37), a distance covered by about 600,000 men on foot, besides women and children.

One of the most famous events of the Exodus was the crossing of the Red Sea (Yam Suph in Hebrew, which can also mean "Sea of Reeds"). As the Israelites fled Egypt, Pharaoh changed his mind and pursued them with his army (Exodus 14:5-9). Trapped between Pharaoh’s forces and the sea, the Israelites feared for their lives. But Moses, following God’s command, stretched out his hand over the sea, and the waters parted, allowing the Israelites to cross on dry land (Exodus 14:21-22). When the Egyptian army attempted to follow, the waters returned and swallowed them, securing the Israelites' escape (Exodus 14:26-28).

This miraculous event not only delivered the Israelites from immediate danger but also established Moses as a prophet and leader, while reinforcing the Israelites' faith in God’s divine intervention (Exodus 14:31).

After crossing the Red Sea, the Israelites entered the Wilderness of Shur (Exodus 15:22). They traveled for three days without finding water, leading to growing unrest among the people. When they finally reached the waters of Marah, the water was bitter and undrinkable (Exodus 15:23). The people complained to Moses, and God instructed him to throw a piece of wood into the water, making it sweet and drinkable (Exodus 15:25).

This incident set the tone for much of the journey through the wilderness, where the Israelites often faced hardships and responded with complaints, while God continuously provided for their needs.

Next, the Israelites arrived at the Wilderness of Sin, between Elim and Mount Sinai (Exodus 16:1). Here, they faced another crisis: lack of food. Once again, they complained to Moses, lamenting their supposed better life in Egypt. In response, God provided manna, a miraculous bread-like substance that appeared every morning (Exodus 16:4-5). This was accompanied by quail in the evening for meat (Exodus 16:13).

The provision of manna, which continued for 40 years, is significant not only as an act of divine sustenance but also as a symbol of God’s ongoing covenant and care for His people, even in times of testing.

One of the most pivotal moments in the Exodus occurred when the Israelites arrived at Mount Sinai (Exodus 19:1-2). Here, they encamped for a significant period, and it was at Sinai that Moses received the Ten Commandments from God, along with other laws that would form the foundation of Israelite society and religion (Exodus 20). This moment marked the formal establishment of the covenant between God and Israel, where God declared the Israelites to be His chosen people if they followed His laws (Exodus 19:5-6).

The giving of the law at Sinai also included instructions for the building of the Tabernacle, a portable sanctuary where God’s presence would dwell with His people as they journeyed through the wilderness (Exodus 25-27).

While Moses was on Mount Sinai receiving the commandments, the people below grew impatient and, under Aaron’s guidance, fashioned a golden calf to worship, echoing the idolatrous practices they had likely seen in Egypt (Exodus 32:1-6). When Moses descended from the mountain and saw the people’s idolatry, he shattered the stone tablets of the law in anger and later had the calf destroyed (Exodus 32:19-20).

This incident was a major test of the Israelites' faithfulness to their covenant with God, and it resulted in severe consequences, including the death of many of the offenders (Exodus 32:28). Nevertheless, Moses interceded on behalf of the people, and God renewed the covenant, demonstrating both His justice and mercy (Exodus 34).

After leaving Sinai, the Israelites continued their journey toward Canaan. However, when they reached the border of the Promised Land at Kadesh-Barnea, they faltered. Moses sent twelve spies to scout the land, and although the land was fertile and abundant, ten of the spies returned with a fearful report about the strength of the inhabitants (Numbers 13:26-33). The people, disheartened, refused to enter Canaan, expressing a desire to return to Egypt (Numbers 14:1-4).

God’s response was to decree that this generation, except for faithful Caleb and Joshua, would not enter the Promised Land. Instead, they were condemned to wander the wilderness for 40 years until the rebellious generation died off (Numbers 14:26-35).

During this period, the Israelites faced numerous challenges, including rebellions, plagues, and divine punishments. Yet, God continued to provide for them through manna, water from the rock (Numbers 20:11), and His guiding presence in the form of a cloud by day and a fire by night (Numbers 9:15-23).

After 40 years of wandering, the Israelites arrived in the plains of Moab, on the eastern side of the Jordan River, opposite Jericho (Numbers 22:1). Here, Moses gave a series of speeches, recapping the journey and the laws, and urging the people to remain faithful to God once they entered the Promised Land. This is recorded in the book of Deuteronomy.

Moses, knowing he would not enter Canaan himself due to his earlier disobedience (Numbers 20:12), appointed Joshua as his successor (Deuteronomy 31:23). Before his death, Moses viewed the Promised Land from Mount Nebo (Deuteronomy 34:1-4), passing leadership to Joshua, who would lead the Israelites across the Jordan and into Canaan.

The journey from Egypt to Canaan was not just a physical journey but a profound spiritual odyssey. The Israelites learned to depend on God for sustenance, guidance, and protection. They received the law, establishing their unique covenant relationship with God, and were prepared for life in the land He had promised them. The story of the Exodus is a foundational narrative for Judaism, Christianity, and Western civilization, emphasizing themes of liberation, faith, law, and divine providence.

Throughout this epic journey, the faithfulness of God to His promises, despite the often wavering faith of the Israelites, stands as a central theme. The path from Egypt to Canaan was marked by miraculous events, divine instruction, and the forging of a people destined to be a light to the nations.

The Geneva Bible: A Cornerstone of English Protestantism A Testament to Reform The 1599 Geneva Bible... Read More

The 21st Century King James Version (KJ21): A Modern Approach to a Classic Text A Balancing Act The ... Read More

The American Standard Version (ASV): A Cornerstone of Modern English Bibles A Product of Scholarly R... Read More

The Amplified Bible (AMP): A Rich and Comprehensive Translation The Amplified Bible (AMP) stands out... Read More

The Amplified Bible, Classic Edition (AMPC): A Timeless Treasure The Amplified Bible, Classic Editio... Read More

The Authorized (King James) Version (AKJV): A Timeless Classic The Authorized King James Version (AK... Read More

The BRG Bible: A Colorful Approach to Scripture A Unique Visual Experience The BRG Bible, an acronym... Read More

The Christian Standard Bible (CSB): A Balance of Accuracy and Readability The Christian Standard Bib... Read More

The Common English Bible (CEB): A Translation for Everyone The Common English Bible (CEB) is a conte... Read More

The Complete Jewish Bible (CJB): A Jewish Perspective on Scripture The Complete Jewish Bible (CJB) i... Read More

The Contemporary English Version (CEV): A Bible for Everyone The Contemporary English Version (CEV),... Read More

The Darby Translation: A Literal Approach to Scripture The Darby Translation, often referred to as t... Read More

The Disciples' Literal New Testament (DLNT): A Window into the Apostolic Mind The Disciples’ Literal... Read More

The Douay-Rheims 1899 American Edition (DRA): A Cornerstone of English Catholicism The Douay-Rheims ... Read More

The Easy-to-Read Version (ERV): A Bible for Everyone The Easy-to-Read Version (ERV) is a modern Engl... Read More

The English Standard Version (ESV): A Modern Classic The English Standard Version (ESV) is a contemp... Read More

The English Standard Version Anglicised (ESVUK): A British Accent on Scripture The English Standard ... Read More

The Evangelical Heritage Version (EHV): A Lutheran Perspective The Evangelical Heritage Version (EHV... Read More

The Expanded Bible (EXB): A Study Bible in Text Form The Expanded Bible (EXB) is a unique translatio... Read More

GOD'S WORD Translation (GW): A Modern Approach to Scripture The GOD'S WORD Translation (GW) is a con... Read More

The Good News Translation (GNT): A Bible for Everyone The Good News Translation (GNT), formerly know... Read More

The Holman Christian Standard Bible (HCSB): A Balance of Accuracy and Readability The Holman Christi... Read More

The International Children's Bible (ICB): A Gateway to Faith The International Children's Bible (ICB... Read More

The International Standard Version (ISV): A Modern Approach to Scripture The International Standard ... Read More

The J.B. Phillips New Testament: A Modern Classic The J.B. Phillips New Testament, often referred to... Read More

The Jubilee Bible 2000 (JUB): A Unique Approach to Translation The Jubilee Bible 2000 (JUB) is a dis... Read More

The King James Version (KJV): A Timeless Classic The King James Version (KJV), also known as the Aut... Read More

The Lexham English Bible (LEB): A Transparent Approach to Translation The Lexham English Bible (LEB)... Read More

The Living Bible (TLB): A Paraphrase for Modern Readers The Living Bible (TLB) is a unique rendering... Read More

The Modern English Version (MEV): A Contemporary Take on Tradition The Modern English Version (MEV) ... Read More

The Mounce Reverse Interlinear New Testament: A Bridge to the Greek The Mounce Reverse Interlinear N... Read More

The Names of God Bible (NOG): A Unique Approach to Scripture The Names of God Bible (NOG) is a disti... Read More

The New American Bible, Revised Edition (NABRE): A Cornerstone of English Catholicism The New Americ... Read More

The New American Standard Bible (NASB): A Cornerstone of Literal Translations The New American Stand... Read More

The New American Standard Bible 1995 (NASB1995): A Refined Classic The New American Standard Bible 1... Read More

The New Catholic Bible (NCB): A Modern Translation for a New Generation The New Catholic Bible (NCB)... Read More

The New Century Version (NCV): A Bible for Everyone The New Century Version (NCV) is an English tran... Read More

The New English Translation (NET): A Transparent Approach to Scripture The New English Translation (... Read More

The New International Reader's Version (NIRV): A Bible for Everyone The New International Reader's V... Read More

The New International Version - UK (NIVUK): A British Accent on Scripture The New International Vers... Read More

The New International Version (NIV): A Modern Classic The New International Version (NIV) is one of ... Read More

The New King James Version (NKJV): A Modern Update of a Classic The New King James Version (NKJV) is... Read More

The New Life Version (NLV): A Bible for All The New Life Version (NLV) is a unique English translati... Read More

The New Living Translation (NLT): A Modern Approach to Scripture The New Living Translation (NLT) is... Read More

The New Matthew Bible (NMB): A Reformation Revival The New Matthew Bible (NMB) is a unique project t... Read More

The New Revised Standard Version (NRSV): A Modern Classic The New Revised Standard Version (NRSV) is... Read More

The New Revised Standard Version Catholic Edition (NRSVCE): A Cornerstone of Modern Catholicism The ... Read More

The New Revised Standard Version, Anglicised (NRSVA): A British Accent on Scripture The New Revised ... Read More

The New Revised Standard Version, Anglicised Catholic Edition (NRSVACE): A Bridge Between Tradition ... Read More

The New Testament for Everyone (NTE): A Fresh Perspective The New Testament for Everyone (NTE) is a ... Read More

The Orthodox Jewish Bible (OJB): A Unique Perspective The Orthodox Jewish Bible (OJB) is a distincti... Read More

The Revised Geneva Translation (RGT): A Return to the Roots The Revised Geneva Translation (RGT) is ... Read More

The Revised Standard Version (RSV): A Cornerstone of Modern English Bibles The Revised Standard Vers... Read More

The Revised Standard Version Catholic Edition (RSVCE): A Cornerstone of English Catholicism The Revi... Read More

The Message (MSG): A Contemporary Paraphrase The Message, often abbreviated as MSG, is a contemporar... Read More

The Voice: A Fresh Perspective on Scripture The Voice is a contemporary English translation of the B... Read More

The Tree of Life Version (TLV): A Messianic Jewish Perspective The Tree of Life Version (TLV) is a u... Read More

The World English Bible (WEB): A Modern Update on a Classic The World English Bible (WEB) is a conte... Read More

The Worldwide English (WE) New Testament: A Modern Take on a Classic The Worldwide English (WE) New ... Read More

The Wycliffe Bible: A Cornerstone of English Scripture A Revolutionary Translation The Wycliffe Bibl... Read More

Young's Literal Translation (YLT): A Literal Approach to Scripture Young's Literal Translation (YLT)... Read More

For enthusiastic readers, managing a collection of books can become challenging. An expanding "to be... Read More

Deuteronomy 18 - "And if you say in your heart, 'How shall we know the word which the LORD has not ... Read More

John 14:26 - "But the Counselor, the Holy Spirit, whom the Father will send in my name, he will teac... Read More

(Enlarge) (PDF for Print) Map of the Origin of Nations and Races that were dispersed by God in Gene... Read More

The Journeys of Abraham (Enlarge) (PDF for Print) - Map of Abraham's Journey with Trade Routes Map ... Read More

(Enlarge) (PDF for Print) Map of the Route of the Hebrews from Egypt This map shows the Exodus of t... Read More

Mark 6:52 - For they considered not the miracle of the loaves: for their heart was hardened. God did... Read More

also see:The Encampment of the Children of IsraelThe Children of Israel on the March THE OUTER COURT... Read More

2 Chronicles 36:23 - Thus saith Cyrus king of Persia, All the kingdoms of the earth hath the LORD Go... Read More

All Bible Maps - Complete and growing list of Bible History Online Bible Maps. Old Testament Maps T... Read More

The Bible portrays marriage as a lifelong bond built on love, faith, and commitment, reflecting God'... Read More

Ancient Manners and Customs, Daily Life, Cultures, Bible Lands NINEVEH was the famous capital of an... Read More

Distances From Jerusalem to: Bethany - 2 milesBethlehem - 6 milesBethphage - 1 mileCaesarea - 57 m... Read More

Dagon was the god of the Philistines. This image shows that the idol was represented in the combina... Read More

Map of Israel in the Time of Jesus (Enlarge) (PDF for Print) Map of First Century Israel with Roads... Read More

The Table of Shewbread (Ex 25:23-30) It was also called the Table of the Presence. Now we will pas... Read More

see also:The PriestThe Consecration of the PriestsThe Priestly Garments The Priestly Garments 'The ... Read More

Introduction to the Book of Daniel in the Bible Daniel 6:15-16 - Then these men assembled unto the k... Read More

The Golden Lampstand was hammered from one piece of gold. Exod 25:31-40 "You shall also make a lam... Read More

The Golden Altar of Incense (Ex 30:1-10) The Golden Altar of Incense was 2 cubits tall.It was 1 cub... Read More

Ancient Tax Collector Illustration of a Tax Collector collecting taxes Tax collectors were very des... Read More

also see: Blood Atonement and The Priests The Five Levitical Offerings The Sacrifices The sacrificia... Read More

Genesis 10:32 - These are the families of the sons of Noah, after their generations, in their nation... Read More

Illustration of Jesus Reading from the Book of Isaiah This sketch contains a colored illustration o... Read More

"But the angel said unto him, Fear not, Zacharias: for thy prayer is heard; and thy wife Elisabeth s... Read More

also see: The Encampment of the Children of IsraelThe Children of Israel on the March The brazen a... Read More

In a rapidly evolving world shaped by both timeless values and groundbreaking technology, individual... Read More

Rome, the Eternal City, has stood as a symbol of history, culture, and religion for over two millenn... Read More

Many teachers assign pieces titled “an essay about god in my life.” The title invites calm thought a... Read More

Exploring identity has become part of the digital life. Social media, streaming, and gaming give you... Read More

Unearth the rich tapestry of biblical history with our extensive collection of over 1000 meticulously curated Bible Maps and Images. Enhance your understanding of scripture and embark on a journey through the lands and events of the Bible.

Start Your Journey Today!