1599 Geneva Bible (GNV)

The Geneva Bible: A Cornerstone of English Protestantism A Testament to Reform The 1599 Geneva Bible... Read More

Maps have long served as more than geographic tools—they are reflections of how people understand their world. Among the most culturally and spiritually significant categories of historical cartography are biblical maps—maps that visualize the geography of the Bible, from the Garden of Eden to the journeys of Paul. These maps provide more than orientation; they are spiritual documents, visual commentaries on sacred texts, and tools for teaching, proselytizing, and devotion. The story of biblical maps is as rich and layered as the scriptures themselves, tracing a path through ancient manuscripts, medieval theologies, Renaissance discoveries, and modern archaeological insights.

The Bible, especially the Old Testament, is rich in geographic references. From the creation story in Genesis to the conquest of Canaan in Joshua, the text is grounded in a physical landscape—Eden, Ararat, Egypt, Sinai, Jerusalem. These locations were not merely background settings but central to the theological and historical narrative.

However, early Jewish and Christian communities did not produce detailed geographic maps. Instead, they relied on textual knowledge, oral tradition, and schematic understandings of the world. This was partly due to religious sensitivities about depicting sacred things visually, and partly because maps, in the modern sense, were not widespread in the ancient Near East.

One of the earliest known attempts to visualize biblical geography is the Madaba Map, a 6th-century mosaic floor found in a church in Madaba, Jordan. This map shows the Holy Land, with Jerusalem at the center, rendered in intricate stonework. While not a "map" in the technical sense, it is a symbolic representation of sacred space and marks a transitional moment when Christian art began incorporating cartographic elements.

During the medieval period, maps were not scientific instruments but theological diagrams. The most famous example is the Hereford Mappa Mundi (c. 1300), which presents the world as a circular diagram with Jerusalem at the center, east at the top, and the Garden of Eden placed near the top. This map is filled with biblical scenes, monsters, cities, and moral lessons.

Medieval biblical maps were intended to affirm the Christian worldview. The earth was seen as a reflection of divine order, and maps were as much didactic tools as geographic ones. The T and O maps, for example, divided the world into three parts—Asia, Europe, and Africa—with a T-shaped river separating them and Jerusalem at the center, illustrating the tripartite division of Noah’s sons (Shem, Ham, and Japheth).

While abstract theology dominated mapmaking, the practice of pilgrimage created a demand for more practical biblical maps. Pilgrims traveling to the Holy Land wanted to trace the footsteps of Christ. Manuscripts such as the Itinerarium Burdigalense (The Bordeaux Itinerary, c. 333 AD) listed stations and holy sites, laying the groundwork for more detailed itineraries and maps in later centuries.

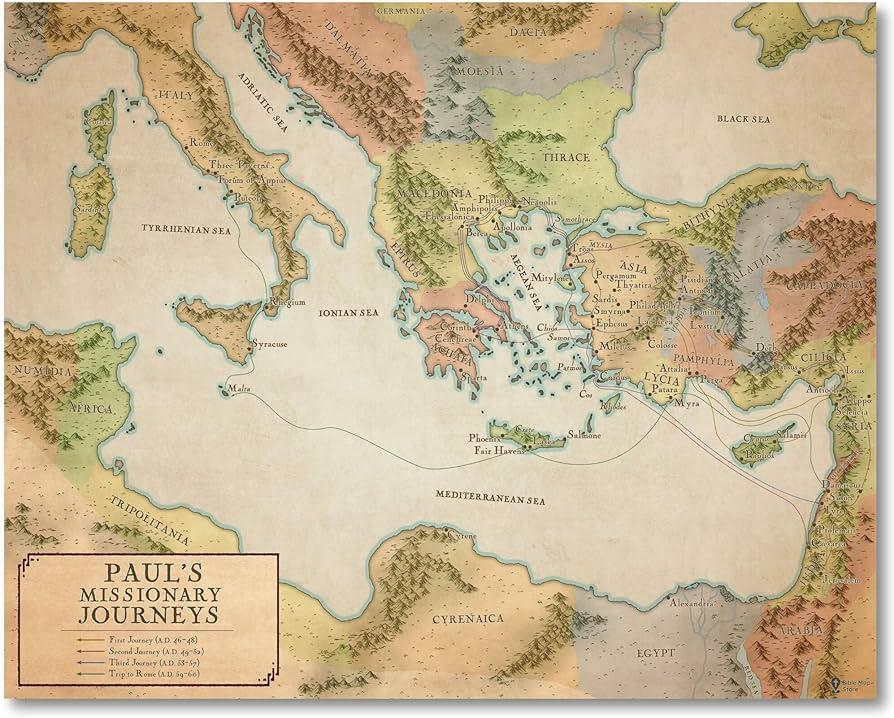

The invention of the printing press in the 15th century revolutionized mapmaking. As printed Bibles became widespread, so too did printed biblical maps. These maps began to combine geographic accuracy with scriptural fidelity. Notable cartographers such as Sebastian Münster, Abraham Ortelius, and Gerardus Mercator included biblical maps in their atlases, charting the Exodus route, the kingdoms of Israel and Judah, and the travels of Paul.

One influential work was Ortelius’ Theatrum Orbis Terrarum (1570), the first modern atlas, which included maps like "Chorographia Terrae Sanctae"—a geographic rendering of the Holy Land.

The Reformation, with its emphasis on sola scriptura (scripture alone), encouraged deep engagement with biblical texts. Protestant scholars sought to make the Bible accessible not only in vernacular languages but also in spatial terms. Biblical maps became essential tools for study and sermonizing. Lutheran and Calvinist Bibles often included fold-out maps showing the locations of biblical events, enhancing theological understanding through geography.

By the 18th and 19th centuries, the rise of empirical geography and archaeology led to renewed interest in matching biblical sites with real-world locations. Scholars and travelers, especially from Europe and the United States, undertook expeditions to the Middle East to verify biblical geography.

Organizations like the Palestine Exploration Fund (founded in 1865) sponsored scientific surveys, producing highly detailed topographic maps of the region. These maps aimed to correlate biblical events with archaeological sites, signaling a shift from symbolic to historical cartography.

Bible maps of this era were also entangled with the politics of empire. Western powers viewed the Holy Land through a colonial lens, using maps to assert cultural and religious superiority. Missionary societies and colonial administrators used biblical geography as justification for political and spiritual conquest, claiming continuity with sacred history.

Today, biblical maps are both academically rigorous and widely accessible. Works like the Oxford Bible Atlas and the Zondervan Atlas of the Bible provide richly detailed maps based on archaeological evidence, climate studies, and ancient records. These atlases serve both scholars and lay readers, often including overlays that show changes in territorial boundaries, trade routes, and population centers across biblical eras.

The 21st century has seen the emergence of digital biblical cartography. Projects such as:

These allow users to interact with maps, click on locations, and see associated scriptures, images, and archaeological data. These tools are transforming biblical education, making geography an integral part of theological study, Sunday school, and seminary curricula.

Biblical maps are windows into the spiritual imagination of generations. They reflect how readers of the Bible, across cultures and centuries, have visualized the sacred narrative in space and time. From symbolic mosaics and medieval diagrams to GPS-tagged archaeological overlays, biblical maps continue to evolve. Yet, they remain grounded in a central purpose: to bridge the text of the Bible with the lived, physical world, helping believers, scholars, and seekers walk the landscapes of faith.

Further Reading and Resources:

The Geneva Bible: A Cornerstone of English Protestantism A Testament to Reform The 1599 Geneva Bible... Read More

The 21st Century King James Version (KJ21): A Modern Approach to a Classic Text A Balancing Act The ... Read More

The American Standard Version (ASV): A Cornerstone of Modern English Bibles A Product of Scholarly R... Read More

The Amplified Bible (AMP): A Rich and Comprehensive Translation The Amplified Bible (AMP) stands out... Read More

The Amplified Bible, Classic Edition (AMPC): A Timeless Treasure The Amplified Bible, Classic Editio... Read More

The Authorized (King James) Version (AKJV): A Timeless Classic The Authorized King James Version (AK... Read More

The BRG Bible: A Colorful Approach to Scripture A Unique Visual Experience The BRG Bible, an acronym... Read More

The Christian Standard Bible (CSB): A Balance of Accuracy and Readability The Christian Standard Bib... Read More

The Common English Bible (CEB): A Translation for Everyone The Common English Bible (CEB) is a conte... Read More

The Complete Jewish Bible (CJB): A Jewish Perspective on Scripture The Complete Jewish Bible (CJB) i... Read More

The Contemporary English Version (CEV): A Bible for Everyone The Contemporary English Version (CEV),... Read More

The Darby Translation: A Literal Approach to Scripture The Darby Translation, often referred to as t... Read More

The Disciples' Literal New Testament (DLNT): A Window into the Apostolic Mind The Disciples’ Literal... Read More

The Douay-Rheims 1899 American Edition (DRA): A Cornerstone of English Catholicism The Douay-Rheims ... Read More

The Easy-to-Read Version (ERV): A Bible for Everyone The Easy-to-Read Version (ERV) is a modern Engl... Read More

The English Standard Version (ESV): A Modern Classic The English Standard Version (ESV) is a contemp... Read More

The English Standard Version Anglicised (ESVUK): A British Accent on Scripture The English Standard ... Read More

The Evangelical Heritage Version (EHV): A Lutheran Perspective The Evangelical Heritage Version (EHV... Read More

The Expanded Bible (EXB): A Study Bible in Text Form The Expanded Bible (EXB) is a unique translatio... Read More

GOD'S WORD Translation (GW): A Modern Approach to Scripture The GOD'S WORD Translation (GW) is a con... Read More

The Good News Translation (GNT): A Bible for Everyone The Good News Translation (GNT), formerly know... Read More

The Holman Christian Standard Bible (HCSB): A Balance of Accuracy and Readability The Holman Christi... Read More

The International Children's Bible (ICB): A Gateway to Faith The International Children's Bible (ICB... Read More

The International Standard Version (ISV): A Modern Approach to Scripture The International Standard ... Read More

The J.B. Phillips New Testament: A Modern Classic The J.B. Phillips New Testament, often referred to... Read More

The Jubilee Bible 2000 (JUB): A Unique Approach to Translation The Jubilee Bible 2000 (JUB) is a dis... Read More

The King James Version (KJV): A Timeless Classic The King James Version (KJV), also known as the Aut... Read More

The Lexham English Bible (LEB): A Transparent Approach to Translation The Lexham English Bible (LEB)... Read More

The Living Bible (TLB): A Paraphrase for Modern Readers The Living Bible (TLB) is a unique rendering... Read More

The Modern English Version (MEV): A Contemporary Take on Tradition The Modern English Version (MEV) ... Read More

The Mounce Reverse Interlinear New Testament: A Bridge to the Greek The Mounce Reverse Interlinear N... Read More

The Names of God Bible (NOG): A Unique Approach to Scripture The Names of God Bible (NOG) is a disti... Read More

The New American Bible, Revised Edition (NABRE): A Cornerstone of English Catholicism The New Americ... Read More

The New American Standard Bible (NASB): A Cornerstone of Literal Translations The New American Stand... Read More

The New American Standard Bible 1995 (NASB1995): A Refined Classic The New American Standard Bible 1... Read More

The New Catholic Bible (NCB): A Modern Translation for a New Generation The New Catholic Bible (NCB)... Read More

The New Century Version (NCV): A Bible for Everyone The New Century Version (NCV) is an English tran... Read More

The New English Translation (NET): A Transparent Approach to Scripture The New English Translation (... Read More

The New International Reader's Version (NIRV): A Bible for Everyone The New International Reader's V... Read More

The New International Version - UK (NIVUK): A British Accent on Scripture The New International Vers... Read More

The New International Version (NIV): A Modern Classic The New International Version (NIV) is one of ... Read More

The New King James Version (NKJV): A Modern Update of a Classic The New King James Version (NKJV) is... Read More

The New Life Version (NLV): A Bible for All The New Life Version (NLV) is a unique English translati... Read More

The New Living Translation (NLT): A Modern Approach to Scripture The New Living Translation (NLT) is... Read More

The New Matthew Bible (NMB): A Reformation Revival The New Matthew Bible (NMB) is a unique project t... Read More

The New Revised Standard Version (NRSV): A Modern Classic The New Revised Standard Version (NRSV) is... Read More

The New Revised Standard Version Catholic Edition (NRSVCE): A Cornerstone of Modern Catholicism The ... Read More

The New Revised Standard Version, Anglicised (NRSVA): A British Accent on Scripture The New Revised ... Read More

The New Revised Standard Version, Anglicised Catholic Edition (NRSVACE): A Bridge Between Tradition ... Read More

The New Testament for Everyone (NTE): A Fresh Perspective The New Testament for Everyone (NTE) is a ... Read More

The Orthodox Jewish Bible (OJB): A Unique Perspective The Orthodox Jewish Bible (OJB) is a distincti... Read More

The Revised Geneva Translation (RGT): A Return to the Roots The Revised Geneva Translation (RGT) is ... Read More

The Revised Standard Version (RSV): A Cornerstone of Modern English Bibles The Revised Standard Vers... Read More

The Revised Standard Version Catholic Edition (RSVCE): A Cornerstone of English Catholicism The Revi... Read More

The Message (MSG): A Contemporary Paraphrase The Message, often abbreviated as MSG, is a contemporar... Read More

The Voice: A Fresh Perspective on Scripture The Voice is a contemporary English translation of the B... Read More

The Tree of Life Version (TLV): A Messianic Jewish Perspective The Tree of Life Version (TLV) is a u... Read More

The World English Bible (WEB): A Modern Update on a Classic The World English Bible (WEB) is a conte... Read More

The Worldwide English (WE) New Testament: A Modern Take on a Classic The Worldwide English (WE) New ... Read More

The Wycliffe Bible: A Cornerstone of English Scripture A Revolutionary Translation The Wycliffe Bibl... Read More

Young's Literal Translation (YLT): A Literal Approach to Scripture Young's Literal Translation (YLT)... Read More

For enthusiastic readers, managing a collection of books can become challenging. An expanding "to be... Read More

Deuteronomy 18 - "And if you say in your heart, 'How shall we know the word which the LORD has not ... Read More

John 14:26 - "But the Counselor, the Holy Spirit, whom the Father will send in my name, he will teac... Read More

(Enlarge) (PDF for Print) Map of the Origin of Nations and Races that were dispersed by God in Gene... Read More

The Journeys of Abraham (Enlarge) (PDF for Print) - Map of Abraham's Journey with Trade Routes Map ... Read More

(Enlarge) (PDF for Print) Map of the Route of the Hebrews from Egypt This map shows the Exodus of t... Read More

Mark 6:52 - For they considered not the miracle of the loaves: for their heart was hardened. God did... Read More

also see:The Encampment of the Children of IsraelThe Children of Israel on the March THE OUTER COURT... Read More

2 Chronicles 36:23 - Thus saith Cyrus king of Persia, All the kingdoms of the earth hath the LORD Go... Read More

All Bible Maps - Complete and growing list of Bible History Online Bible Maps. Old Testament Maps T... Read More

The Bible portrays marriage as a lifelong bond built on love, faith, and commitment, reflecting God'... Read More

Ancient Manners and Customs, Daily Life, Cultures, Bible Lands NINEVEH was the famous capital of an... Read More

Distances From Jerusalem to: Bethany - 2 milesBethlehem - 6 milesBethphage - 1 mileCaesarea - 57 m... Read More

Dagon was the god of the Philistines. This image shows that the idol was represented in the combina... Read More

Map of Israel in the Time of Jesus (Enlarge) (PDF for Print) Map of First Century Israel with Roads... Read More

The Table of Shewbread (Ex 25:23-30) It was also called the Table of the Presence. Now we will pas... Read More

see also:The PriestThe Consecration of the PriestsThe Priestly Garments The Priestly Garments 'The ... Read More

Introduction to the Book of Daniel in the Bible Daniel 6:15-16 - Then these men assembled unto the k... Read More

The Golden Lampstand was hammered from one piece of gold. Exod 25:31-40 "You shall also make a lam... Read More

The Golden Altar of Incense (Ex 30:1-10) The Golden Altar of Incense was 2 cubits tall.It was 1 cub... Read More

Ancient Tax Collector Illustration of a Tax Collector collecting taxes Tax collectors were very des... Read More

also see: Blood Atonement and The Priests The Five Levitical Offerings The Sacrifices The sacrificia... Read More

Genesis 10:32 - These are the families of the sons of Noah, after their generations, in their nation... Read More

Illustration of Jesus Reading from the Book of Isaiah This sketch contains a colored illustration o... Read More

"But the angel said unto him, Fear not, Zacharias: for thy prayer is heard; and thy wife Elisabeth s... Read More

also see: The Encampment of the Children of IsraelThe Children of Israel on the March The brazen a... Read More

In a rapidly evolving world shaped by both timeless values and groundbreaking technology, individual... Read More

Rome, the Eternal City, has stood as a symbol of history, culture, and religion for over two millenn... Read More

Many teachers assign pieces titled “an essay about god in my life.” The title invites calm thought a... Read More

Exploring identity has become part of the digital life. Social media, streaming, and gaming give you... Read More

Unearth the rich tapestry of biblical history with our extensive collection of over 1000 meticulously curated Bible Maps and Images. Enhance your understanding of scripture and embark on a journey through the lands and events of the Bible.

Start Your Journey Today!